News

Defining Scents – on the scientific background work for Katie Paterson’s commission

The Scottish artist Katie Paterson’s IHME Helsinki 2021 public artwork To Burn, Forest, Fire consists of the scent of the first forest on our planet and the scent of the last forest of the age of climate crisis. These scents have been processed into incense, which were burned in different parts of Helsinki during September 2021.

In the spring, we published a news story about the scientific background work on the definition of a forest. In this article we reporton research and research methods related to the definition of the scents in this special artwork.

Katie Paterson Studio conducts long-term background work with researchers, whose job descriptions correspond to the scientific area of expertise relevant to each work of art. Ideas for works emerge from Paterson’s imagination, but the refinement of these ideas into real, finished works of art is guaranteed by the results of scientific research. In the end, however, it must be remembered that, at best, the answers to the questions asked are often what are known as “the best enlightened estimates”.

The scent of the first forest

The experience of a scent is caused by a chemical compound or a mixture of several compounds from which molecules evaporate into the air. Fragrances are usually named after their source, but no scientific “basic scents” have been defined for fragrances. Human beings detect fragrance molecules in the olfactory epithelium of the nose, from where their chemical information is transmitted electronically along the olfactory nerve to the cortical layers of the brain. Humans can recognize more than ten thousand scents.

Chris Berry is a palaeobotanist who specializes in the first forests of the Devonian period. He favours the choice of the Cairo Forest in New York State as the first forest in the mid-Devonian period, and has a strong argument for this. One of the trees found there, Eospermatopteris (Cladoxylopsida), is widely agreed among researchers in the field to be the “first tree”.

The first root fossil finds are from low-growing, lycopsids and evidence has been found of woody plants with extensive roots and thick trunks from a little later on. Judging by the fossils, the fern-like tree of the genus Eospermatopteris, the giant tree (Giant clubmoss) and the distant precursor of the genus Archaopteris, which left the most impressive root fossils, can be traced back to these early forest species.

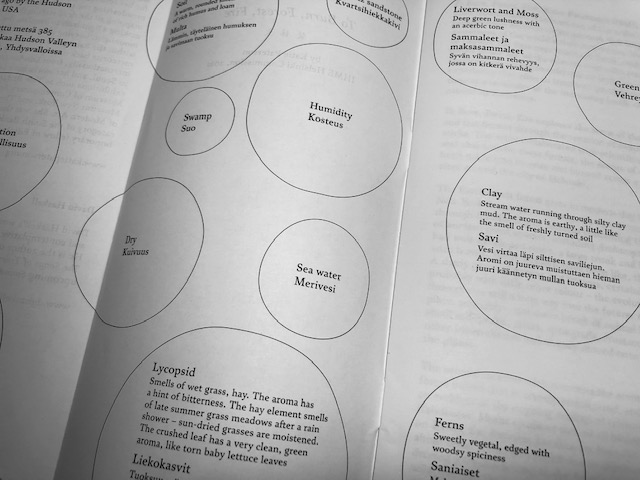

What did it smell like in that first forest, which did not yet have vertebrates or flowers? Based on discussion with researchers, the following description was reached: the first forest smelt of soil, stone, salt, clay and algae. The above-mentioned lycopsids smelt of wet grass, hay with a hint of bitterness. The hay element smells like late summer grass meadows after a rain shower – similar to the sun-dried grasses that have been moistened. You can also find the scent of the crushed leaf that has a very clean, green aroma, resembling the smell of a torn baby lettuce leaf.

The scent of the last forest

As expected, the Amazon rainforest was chosen as the last forest of our time in Katie Paterson’s artwork. The Amazon’s forests and diversity are threatened by intensive agriculture and livestock farming, power plants and dams. The disappearance of the Amazon rainforest is also accelerating the climate crisis: rainforests are a significant carbon sink. The Amazon rainforest covers an enormous area, about 5.5 million square kilometres. In Paterson’s project, one location was chosen to represent the Amazon rainforest: the Tiputini Biodiversity Station in the Yasuni Biosphere Reserve in Ecuador.

“Scientists estimate that this part of the Amazon is the home to the highest density of species anywhere, a conclusion derived from studies of the numbers of plants and animals found within Yasuni. The six hundred species of birds and more than one hundred species of amphibians in the Yasuni area represent the most diverse communities of these species in the world, supported by four thousand known plant species,” writes Professor David Haskell in the booklet that sheds light on the scientific background work done for the artwork.

What does it smell like in this vanishing, last forest of our time? It smells, among other things, of small tropical Inga trees, wet clay, decaying vegetation, the sweetness of the fruit of the guava tree and the nutmeg aroma of the bark of the trees. To determine the scents, Katie Paterson Studio conducted a survey with indigenous guides working at the Tiputini research station. In addition to the scents of vegetation, trees and fruit, the forest also smelled of animals: the smell of a howler monkey that is reminiscent of the smell of cow pasture, the smell of armadillos that is reminiscent of the smell of cilantro and spoiled raspberries, the smell of peccary pigs that is reminiscent of the smell of concentrated, salty broth, and even the smell of bed bugs and tiger beetles that is reminiscent of the smell of bubble gum. Pretty wonderful, isn’t it?

Scent diagrams can also be found here >>

Read more about the research background to the booklet in an article in Geologi magazine >>